By the spring of 1945,the Red Army had driventhe Nazis out ofHungary.The war came to an end,butthe losses were staggering. Ten percent of the population had perished; the country was in ruins. People had to start a new life, and the country had to be reorganized.

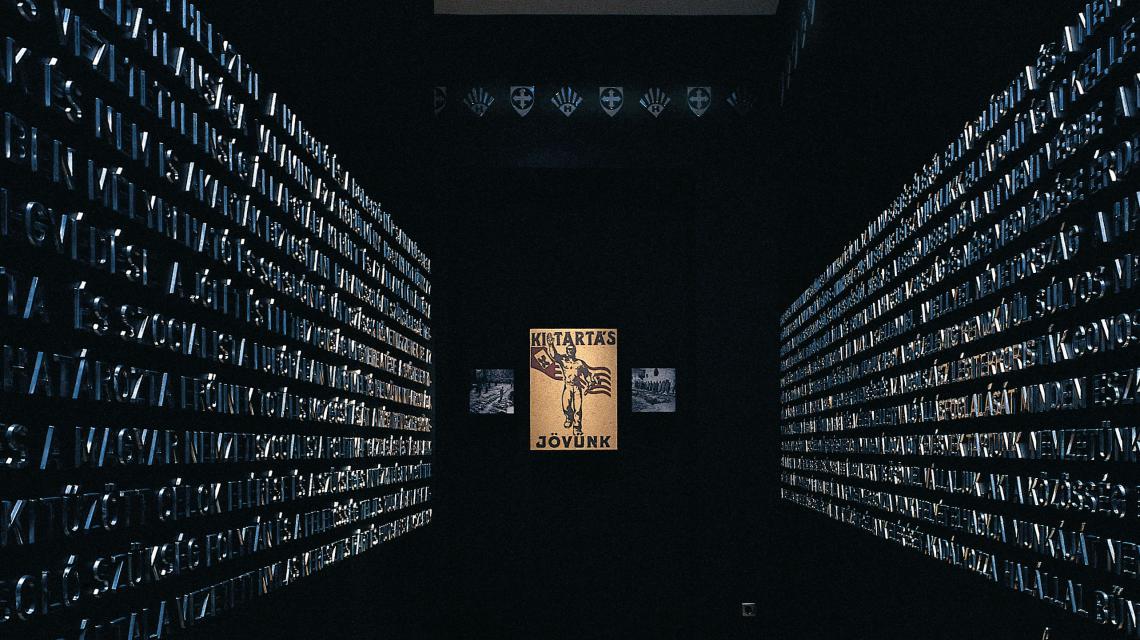

“Every single action we took was a blow to the secret plans of the American imperialists, Tito, his associates and their Hungarian hirelings.”

Hungary’s communist dictator Mátyás Rákosi in 1949

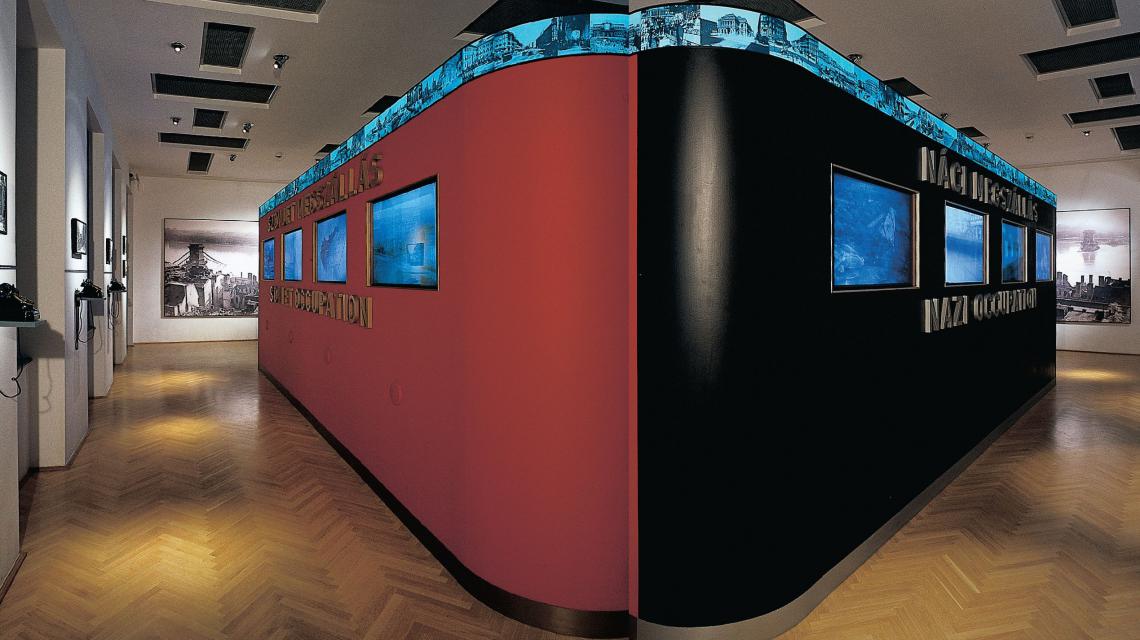

After World War II, the Soviet dictator and mass-murderer Joseph Stalin called for the immediate introduction of communism in our country. While the Nazis had put the Arrow Cross in power, the Soviet invaders relied on local communists and those returning from Moscow. In Hungary, however, they had their work cut out. After World War I the Hungarian Soviet Republic had subjected the country’s citizens to a communist reign of terror lasting 133 days, and Hungarians did not want to be part of another Marxist human experimentation project. The communists could only achieve their aims with the support of the occupying Soviets, electoral fraud and outright violence. In 1945 Soviet pressure had already delivered them the Interior Ministry – and with it control of the police. The era of fear and terror began. Opponents of the communists were arrested or expelled from the country on trumped-up charges, and democratic political parties were obstructed by a variety of means. Finally we were subjected to a party dictatorship of the state based on a one-party system.

Meanwhile, communist propaganda trumpeting its “success” went into overdrive. The news on the radio, in the press and in cinemas only reported successes and extolled the genius of the leader, Mátyás Rákosi. But behind the scenes repression, violence and terror became part of everyday life. Everyone was under surveillance, with informants being assigned to them. The political police – with their tens of thousands of agents, informants, prison guards and thugs – made sure that no one would think of opposing the will of the occupiers and their Hungarian comrades.